Category Archives: Update 9

A myth corrected to – Haworthia maculata var. livida (Bayer) Bayer – and flowers ignored.

(Haworthia maculata var. livida (Bayer) Bayer, comb.nov. H. pubescens var. livida Bayer in Haworthia Revisited, p.134, 1999, Umdaus) Type: Cape-3319 (Worcester): S Lemoenpoort (-CD), Bayer 1128 (NBG, Holo.).

I described Haworthia pubescens var. livida in Haworthia Revisited (Umdaus, 1999), in the full knowledge that it was in a twilight zone of inadequate information. It is a good example of how Latin names give plants a false reality. The system forces decision making without any slack being cut for doubt. This is thus a good opportunity to demonstrate what inexperience and ignorance add to the process of classification. In the small area along the Breede River north of the Brandvlei Dam near Worcester, the species H. herbacea, H. maculata and H. pubescens grow in close proximity. H. herbacea is ubiquitous throughout the Worcester/Robertson Karoo, while H. maculata has a curious distribution in that area. It occurs at widely separated localities on the western fringe of H. herbacea and I have wondered about its relationship to that species because of the similar flowers and flowering time. H. pubescens is only known from a small set of low ridges east of the Brandvlei Dam where it grows in close proximity to H. herbacea. It also has similar flowers but it flowers a little later in late spring as opposed to early spring.

A myth corrected – part 2

Set 3. Map point 5.

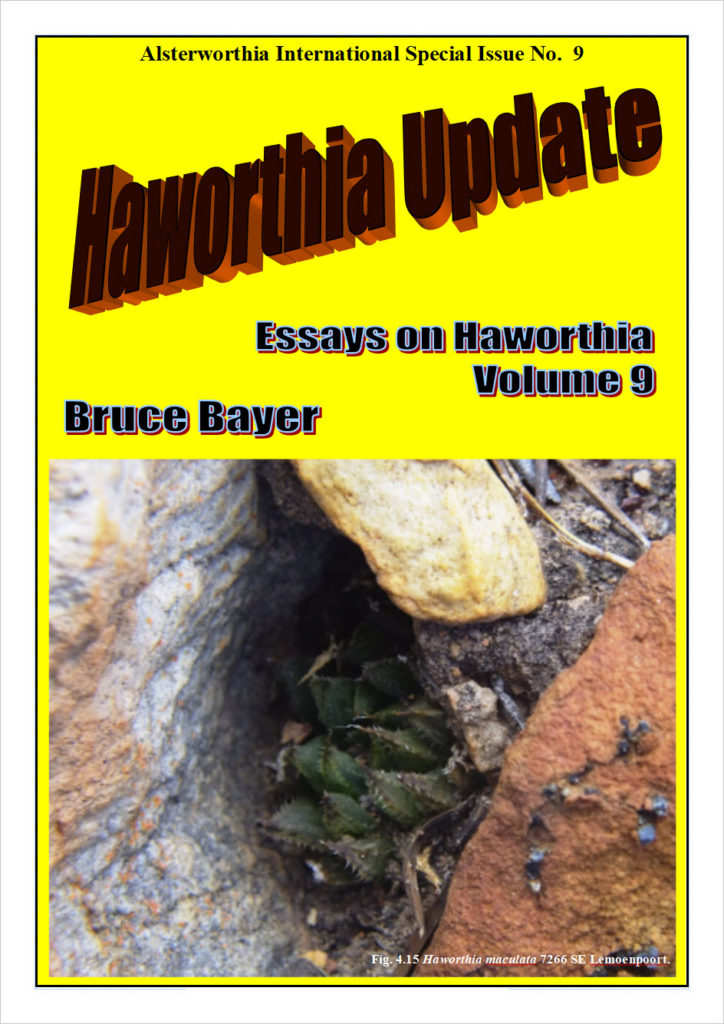

Figs. 3.1 to 3.34 MBB7066 H. maculata, Lemoenpoort.

This is the type locality (ie. MBB1128, W. Lemoenpoort) for H. maculata var. livida that I think is largely untenable or unnecessary fragmentation. Lemoenpoort is the valley that separates Hammansberg from Ouhangsberg. The first few plants seen were in exposed situations and had the purplish or bluish-grey colour that prompted the latin name. This was maintained in cultivation. I linked it at the time to H. pubescens that seemed more probable at the time than to H. maculata and then simply because of the perceived demands of a relatively inflexible nomenclatural system. There are now seven new populations that contribute and improve understanding of H. maculata as a species. All these localities are in Witteberg Sandstone and the type locality is only slightly different in that the stratum of rock is less feldspathic (i.e. mineralized).

A myth corrected – part 3

Set 5. Map points 6, 9, 13, and 14. Ouhoekberg.

Figs. 5.1 to 5.24 MBB7991a H. maculata, Ouhoekberg E.

Figs. 5.25 to 5.28 Panoramic views.

Figs. 5.29 to 5.33 MBB7991b H. maculata, Ouhoekberg.

These populations were first observed as one on a higher eastern point of the Ouhoekberg above Moddergat in about 1975. George Lombard accompanied Kobus Venter and me there in 1996 and we found them on the western high point. I located them nearby in 2004. We found them again recently as two more populations on the eastern heights near where I must have observed them first. Note the reticulation in the dried fruit capsule. It can be very much more evident in species like H. pulchella but I seriously doubt its diagnostic value. I have included views to… (a) north to show the water of the Brandvlei Dam in the far distance. The area between has not been adequately explored. What is interesting is the geology. The mountains on the left are the Table Mountain Sandstones, nearer is the valley where the soft Bokkeveld Shale has been eroded away, and then comes the Witteberg Sandstone with a neck of soft shale, and then low down is Dwyka tillite. H. herbacea is present on the Dwyka outcrop barely visible in the middle right. (b) The second view is looking east at first the Hammansberg and beyond that Ouhangsberg with H. mirabilis on its eastern flanks. The view looking southeast is over low Bokkeveld shale ridges with an abundance of H. herbacea. The view south is to Villiersdorp where Wolfkloof (not the Robertson Wolfkloof) is a deep valley behind the Table Mountain Sandstone left of the gap through the Rooihoogte Pass. Here is where H. herbacea ‘lupula’ occurs, unusually in sandstone. Altitude and skeletal soils of different origins contribute hugely to the genetic mosaic. Arable depositional soils exclude Haworthia and obviously inhibit contact between populations.

A myth corrected – part 4

Set 7. Map point 11. Cilmor.

Figs. 7.1 to 7.3 MBB7271

An interesting point here that H. herbacea (map point 18) occurs between this point and all the Die Nekkies populations. I am not sure that the area between can be fully explored although I have been into it.

A myth corrected – part 5

Set 10. Map point 18. H. herbacea ‘submaculata’. Brickfield, Brandvlei Dam.

Figs. 10.1 to 10.20 MBB7995 H. herbacea, S Brandvlei Brickfield.

Figs. 10.21 to 10.53 MBB7996 H. herbacea, E Brandvlei Brickfield.

I have associated this locality with vonPoellnitz H. submaculata and treated it as a synonym of H. herbacea. However, here I first illustrate a population about 600m south of that where the plants are in the usual size range for the species ie.30-40mm diam. At the locality east of the Brickfield and next to the Breede River, the plants are 1/3 to 1/2 as large again and can form huge clumps. North-west from this is a population of H. maculata at the extreme end of Die Nekkies and only about 300m distant, and this population I have always regarded as somewhat intermediate. What is interesting to note is the huge variation in leaf shape and armature within each population. In both cases the plants are in Witteberg Sandstones and at the first site this is both in a very shale-like stratum as well as in a highly quartzitic one. This is unusual for H. herbacea. Both populations wedge in geographically between H. maculata populations and in no known case do both occur.

My view of names

There seems to be so much harping about my departure from the International Code of Botanical Nomenclature (ICBN) that I obviously need to try and explain myself better. The real issue is that we are dealing with a group of plants that is largely appreciated for its vegetative characters and not for its small and unexceptional flowers. Because the plants are small and so commonly grown by collectors the numbers of plants in cultivation and close observation is large. The plants also do vary in respect of leaf morphology, arrangement, and surfaces to a greater extent than in many other genera. Furthermore, the variation is also exaggerated by growing conditions. The fact that flowers are not used in the classification process beyond the level of sub-genera means that there is an almost total reliance on vegetative characters for classification. The nomenclatural system in botany tends to be a typological one, which means that reliance is placed on descriptions very often derived from single specimens. This is particularly so when the nomenclatural types are simply old illustrations that have been used to arrive at identifications and names by consecutive authors for decades. Thus use of those identifications and names, and their continuing re-interpretation causes a great deal of either grief or great personal satisfaction depending on just who is being affected by the process. The fact that the names should indicate “species” is lost from sight and totally obscured by the additional absence of any good universally accepted explanation for what a species is or might be.

Explanation in and around all this has been a large part of my writing since I started this in 1962. Thus I will not enlarge on the subject but rather try to explain again this way using a species name generated by Col C. L. Scott with whom I had some considerable altercation. It must be understood that Col Scott was not a biologist and it is just a simple fact that the problems that the above brief remarks expose, trouble many professional taxonomists to this day. I do not condemn Col Scott and express my respect and admiration for him and am very grateful to him for the friendship he later extended to me before he died.

The example I will take is that of his species Haworthia geraldii. It comes from a small hillside east of Riversdale running south to north, named Komserante. This is an Afrikaans term meaning the ridge around a small geographic basin. In the way that Haworthias are assembled in small habitat defined and localised populations, there are three recognizable populations of plants (of the subgenus Haworthia) along this one ridge about 1km long. The southern population used to be complemented by still another that occurred where the stream bed left the basin at the southern end. A plant from that southern population was named as H. foucheii by K. Von Poellnitz. The northern population is a bit problematic and I initially included it in my then concept of H. magnifica. Since then however, it has become clear to me that my idea of species was too conservative and that H. magnifica as described by Von Poellnitz from south east of Riversdale (now the Frehse Reserve) is part and parcel of a huge complex that I regard as H. mirabilis.Thus this northern population is seen by me as H. mirabilis but complicated by the fact that it is largely influenced by hybridization with the next population or populations south. A plant (or perhaps, and doubtfully, plants) have been given the name H. vernalis by the Japanese writer M Hayashi. The name H. geraldii is attached to the second population southwards. The plants are very proliferous, form large clumps and the leaves are usually quite strongly retused (“bent back like a thumb”). The name H. foucheii is simply attached to the third because the plants there tend to be solitary and the leaves are also fairly erect and spreading as described and pictured for the original from the fourth population that was off the ridge.

The problem is now that we have descriptions and plants in each population that do not match the descriptions. While I assign the northern population and all the plants in it to H. mirabilis, other writers use the names H. vernalis, H. magnifica and even the confused name H. asperula. What they mean is by no means clear and in actuality a lot more names and descriptions would then be required to name each of the countless variants there for what might be an original pure species and variants or for first second or third generation hybrids with H. geraldii or H. foucheii as those names were applied.

But the problem is far more extensive than just these four populations. After years and years of field exploration it has become evident to me that like H. mirabilis, H. retusa is also highly diverse and I see it to include all the variants of H. turgida. In fact I suggested a long time ago that H. retusa is simply the solitary large form of H. turgida in low-lying level areas as opposed to the more common and extensive clumping cliff dwelling forms of that species. This is also why I object to the requirements of the ICBN that require the name H. retusa to take precedence for the species for historical reasons when it would be far more realistic to take it as a variant of H. turgida for biological reasons.

It has always been simply evident to me that H. geraldii and H. foucheii are variants of H. retusa. The problem now is that the plants in the two populations vary so much that, while the names are indeed useful for commercial and collector use, there can be problems that the use and application of the names will be confused.

Look at it like this. In respect of H. geraldii; it came from one population at Komserante, Riversdale and not all the plants are the same. I think this one population and all those plants in it belong to the species H. retusa, so I called it H. retusa var. geraldii. (var. = variety). Because not all the plants look the same that means that only some are truly geraldii and only the plants that meet Scott’s description are actually var. geraldii. Because the plants multiply vegetatively and Scott only took a piece, the original plant may still be there. This means that we should recognize it as H. retusa var geraldii forma geraldii and in cultivation as H. retusa ‘Geraldii’ or just as H. ‘Geraldii’. What do we do with the other 100 plants or more in the population that are not H. retusa ‘Geraldii’? I do not think they can all get names so I take away the capital letter, leave out “var.” and use ‘ and ‘ (inverted commas) to show that the identification is, and will, be a bit uncertain unless you know from a label that the plant comes from that particular population at Komserante. The same applies to H. retusa var foucheii. In this case the original population is gone and I am not sure if H. ‘Foucheii’ is still in cultivation. So I use the name H. retusa ‘foucheii’ for a second population on Komserante. Some of the plants in this population look like some of those in the H. retusa ‘geraldii’ population but not quite like H. ‘Geraldii’ itself. So for me the answer is MBB7780 H. retusa ‘geraldii’, Komserante and MBB7781 H retusa ‘foucheii’, Komserante.

It can be seen that a complication comes in when more than one population is involved. The problem then is that you can put them in a line so that some plants in the first population look like plants in the second, some in the second look like plants in the third, some of those look like those in the fourth until at the end none of the plants in the last population look like any in the first. The trouble in the field is that the line is not straight and it can also go off in different directions. Some of those directions may end up where they started. One simply cannot be truly confident about many of those names that are given to plants. Serious and proper consideration must be given for how different they may be even within the populations. Not to say of the shared similarities and still added variation from geographically adjacent populations. It may happen that I may write H. ‘retusa’ (and add number and place name) for a population that may better (not necessarily correctly) be identified as H. retusaXmirabilis. Other writers who are not biologists and have other considerations in mind may want to give a new name altogether. That new name and description may be again really only for one plant, or maybe a few more in a population, that have real or imagined novelty value and attraction. But they take no account of all of the less attractive variants or other populations that comprise the biological whole by close proximity if for nothing else.

The above discussion is integral to the rationalized list of names that Dr John Manning helped me produce. There are some species names there that I have deliberately presented as synonyms or variants of the species I recognize, because the authors of those names fail to convince me that they have any understanding of the situation at all. The word “species” is apparently simply a convenient naming system for oddities and novelties and not any scientific construct to explain the natural phenomena of living systems and their parts.

To summarize; I have written a report on flower characters in which I refer to the Komserante populations and I have used the following names and my own convention as follows:-

Please note that the way I have omitted the word variety from the following names and also used inverted commas …

7779 H. mirabilis, Komserante (the northern population – I could add ‘vernalis’ but it carries all the baggage of doubt about actual status).

7780 H. retusa ‘geraldii’, Komserante.

7781 H. retusa ‘foucheii’, Komserante.

7920 H. retusa ‘ nigra’,, Van Reenens Crest.

The omission of the word variety is for two reasons…

1. Economy

2. To convey the idea that the actual indication of status is not certain as I have used the name to indicate a population or populations rather than a single described plant. The prime and overriding uncertainty is that we cannot know what a species is that I have described for Haworthia. Thus how can we possibly rank populations at levels below?

The use of inverted commas reinforces what I want to convey. This is that the individual plants in the populations are variable and it may not be easy to always identify the plants (individual or population) according to a more formal classification.

Any departure from the ICBN or the way the names are treated in formal botany conveys the difficulty that I personally find in trying to reconcile formal nomenclature with names that are so often tied to single plants.

Haworthia Update Vol. 9 – Addendum

The data keeps coming …