Printed in National Cactus and Succulent Journal, 28:80(1973).

Part 3. HAWORTHIA REINWARDTII Haw. and HAWORTHIA COARCTATA Haw.

M. B. Bayer, National Botanic Gardens of South Africa, Karoo Gardens, Worcester.

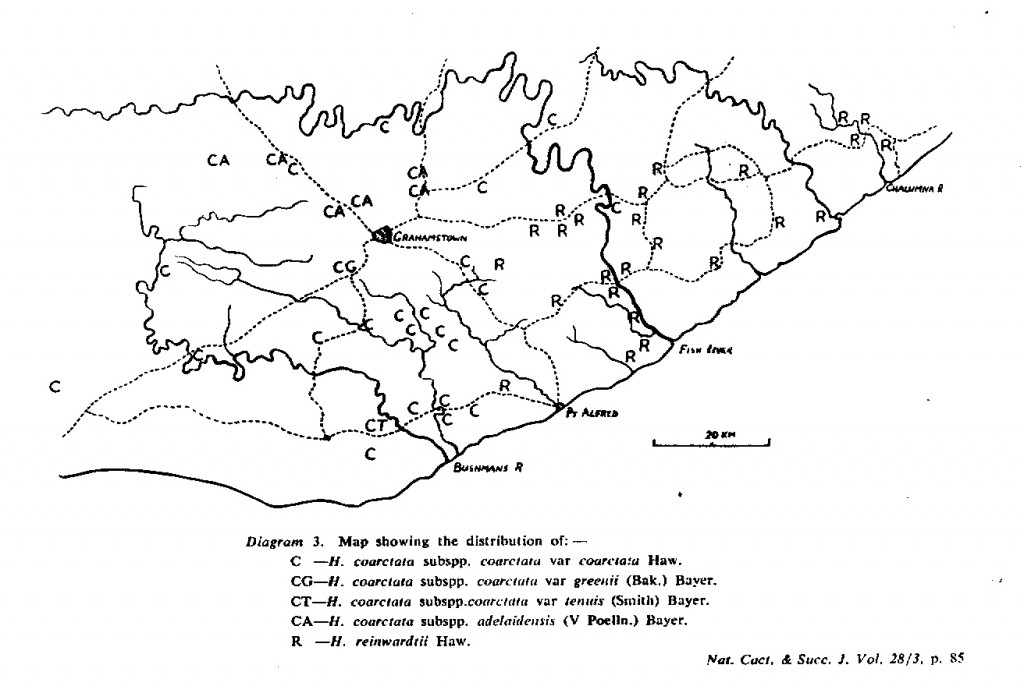

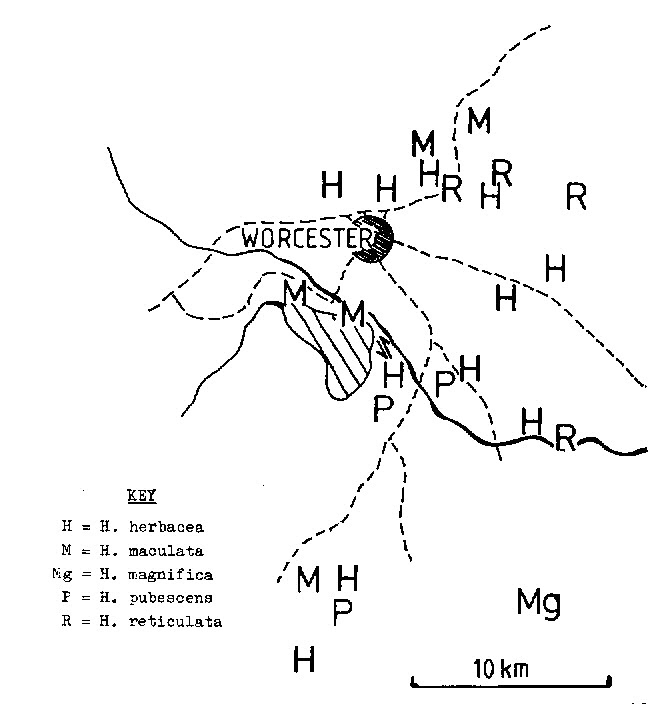

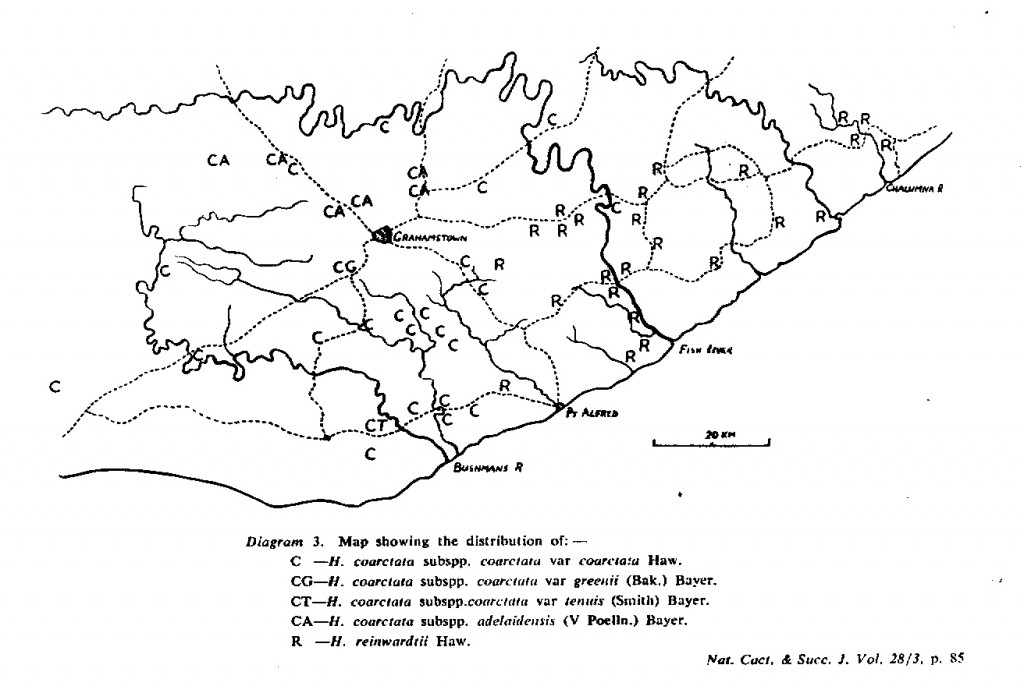

Abstract: The names Haworthia reinwardtii Haworth and H. coarctata Haw. are upheld for two related species occumng in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. The species names H. fulva Smith, H. musculina Smith, H. baccata Smith. H. peacockii Baker and H. coarctatoides Resende et Viveiros are rejected as superfluous. H. coarctata subsp. adelaidensis (Von Poellnitz) Bayer stat.nov., H. coartata subsp. coarctata var. greenii (Baker) Bayer stat.nov. and H. coarctata subsp. coarctata var. tenuis (Smith) Bayer stat.nov. are the only infra-taxa recognised. The many varieties of H. reinwardtii previously upheld are, recognised as forms within the two accepted species. A map showing the distribution of the taxa is given.

Introduction: Considerable doubt most exist that all the varieties of H. reinwardtii Haw. are really necessary. Unfortunately such doubts are seldom associated with a rationalised expectation of what varietal differences should express. It has already been shown that problems in Haworthia taxonomy can only be resolved by the adoption of a realistic species concept. The object of this paper is to report on the field investigation into the distribution and variation of H. reinwardtiii and its allies, with observations on population structure within this complex.

The species involved in this study are all in the Section Coarctatae Berger, and include H. baccata Smith, H. coarctata Haw., H. coarctatoides Res. et Viveiros, H. fulva Smith. H. greenii Baker, H. musculina Smith, H. peacockii Bak., H. reinwardtii and varieties of these. Apart from Smith’s species, original localities are not recorded.

Investigation: Attention was confined to the Eastern Cape, in the area extending from Addo in the west to East London in the east, and from the southern sea coast to the Fish River in the north. As for other species of Haworthia, it was found that plants are nearly always confined in small localised populations of varying densities. No particular correlation of distribution with vegetation type or geological formation was observed, and plants were recorded from sea-level to 650m through four main vegetation types and three geological systems. Distribution is primarily associated with rocky, well-drained situations and reduced competition from other vegetation. This latter point is by no means always true, as for example H. reinwardtii var. tenuis Smith, growing in deep soils under a dense canopy of Valley Bushveld vegetation. Similarly, as the name implies the origin of H. greenii var. silvicola Smith was also sylvan. Fifty-three collections were made at different points throughout the area, paying particular attention to localities for recognised varieties where known. Of these, only H. reinwardtii var. peddiensis Smith was not recollected. In each case up to ten pieces of full- length leafy stem were collected from separate plants at each site. Judgement of the taxonomic position is thus based on field impressions, collections made personally by the writer, twelve collections made by Mr F. J. Stayner, 31 single plant collections still extant in Smith’s collection after 30 years, and on herbarium specimens in the Albany Museum, Grahamstown, the Compton Herbarium, Kirstenbosch and the Bolus Herbarium, University of Cape Town.

Attention is drawn to specimens in the Bolus Herbarium; H. Viedge April 1927 from “Tabase’ near Umtata”, a sparsely tubercied and steeply spiralled plant like H. coarctata, R. C. Holmes August 1935 from ‘between Kei and Tsomo Rivers” which is akin to H.. attenuata Haw., and a glabrous leaf remnant, Pillans November 1906, from “between King Williamstown and Grahamstown”. Neither of the latter specimens can be confidently allied to present known taxa, and the Umtata specimen in particular represents a complete contradiction in terms of the known distribution of the genus.

In the case of H. baccata. a thorough search was made in the Isidenge area of the Stutterheim district before concluding that the locality was a most improbable one. It was subsequently learned from Mr W. E. Arrnstron (a well-known collector) that the plant had not been collected at Isidenge but in fact came from Frazers Camp near Grahamstossn. The plant came in Smith’s possession at third-hand and there is thus reason to question the given locality. Interpretation of observations presented here was subject to particular consideration of both phenotypic and genotypic variation. Phenotypic variation is the outward appearance of the individual as it responds to factors in the environment. Comparison of specimens collected from the same sites as plants growing in Smith’s collection showed surprisingly little differences. Attenuation resulting from shading was seldom encountered and it was nearly always possible to observe plants at each locality in demonstrably steady growth states. More difficult were certain localities where combinations of rock substrate and shade produced more variable growth conditions.

As far as the genotype – the fixed genetic basis of variability – is concerned, the problem also appears relatively slight, despite the high percentage of polyploidy noted by Riley (1968). Riley suggested that polyploidy may account for the large number of taxonomic varieties in H. reinwardtii, or alternatively because differences between these are small, that they may have arisen as single gene mutants which have propagated vegetatively. Riley and Mukurjee (1965) recorded 4 diploids, 8 tetraploids and 1 aneuploid. These are H. fulva, H. reinwardtii vars. olivacea Smith, tenuis Smith, haworthia Res. (= reinwardtii) with 2n =14; H. baccata, H. musculina, H. greenii var. silvicola, H. reinwardtii vars. huntsdriftensis Smith, valida Smith and an unnamed variety with 2n=28:

and H. greenii forma pseudocoarcata (VP) Res. with 2n=28 and 30. In 1962 (Riley,1968) these authors also recorded the aneuploid H. reinwardtii var. chalwinii (Marl. et Berg.) Res. with 2n=26. Resende and Pinto-Lopes (1946) recorded the following: H. reinwardtii vars. adelaidensis VP., triebneri VP, minor Haw. and major Haw. 2n= 14: H. reinwardtii vars. conspicua VP, fallax VP, haworthia, chalwinii, H. greenii forms greenii, minor and pseudocoarctata 2n =28: H. reinwardtii var. archibaldiae VP 2N=21; H. coarctata vars. coarctata, kraussii Res. and coarctatatoides Res. et Viv. nom. nud. 2n=42.

Where these records can be referred to field populations, it appears that diploids and polyploids are encountered across the range of the species complexes. Thus polyploidy is not conclusively a basis of species or varietal differentiation in this group. If it were so, one would expect some evidence of discrete sympatric populations – which is definitely not the case for example, at ‘Hopewell’, Bathurst. Here H. fulva, H. musculina and H. greenii var. silvicola all have their origin in the same close locality. Smith’s field notes, in which he also recorded H. coarctata, H. chalwinii and H. reinwardtii from the same locality, put the three taxa into proper perspective. Apart from the fact that H. musculina and H. greenii var. silvicola have been cited as tetraploids, as opposed to H. fulva which is diploid, these three taxa do not command separation if indeed recognition at the level of forms. H. coarctatoides is a nomen nudum for a plant said to be intermediate between H. reinwardtii and H. coarctata and can be rejected as a meaningless taxon.

Only one locality was found presenting any real evidence of two non.-interbreeding entities growing together. This is at Hellspoort where one of these entities is allied to H. coarctata and may thus be hexaploid (or perhaps only tetraploid following Resende’s notes on the locality for H. greenii forma pseudocoartata at Alicedale, a plant which the writer allies with his interpretation of H. coarctata), and the other to H. reinwardtii var. adelaidensis which is diploid. The latter variety can be shown to be correctly related to H. coartata at subspecies level. An interesting point is the occurrence of sterile or at least partly sterile triploids in the H. reinwardtii vars. archibaldiae. chalumnensis Smith and peddiensis (Riley, private communication). The writer particularly noted two populations in which it appeared that despite normal flowering, ovules were aborting. This does bear on Riley and Majumdar’s (1966) statement that Haworthias usually propagate vegetatively. While as a general stalement this is incorrect, it is clearly to some extent true for some species including H. reinwardtii and H. coarctata. Vegetative reproduction could perhaps account for uniformity at different sites if populations had their origins in single clones, or alternatively one would expect more discontinuity where several genotypes were involved. Variability at various sites and clinal trends across the distribution range, in the writers opinion, tend to detract from vegetative propagation as a factor in population differentiation. In support of this comment is the observation on locality restrictions where it is felt that movement of detached stems would surely lead to positive downward migration of populations. Yet it is a feature of the species, particularly nearer Grahamstown and notwithstanding earlier comments, that they occupy elevated positions on edges of ridges and plateaus. Nevertheless there is adequate evidence that vegetative propagation does occur especially under conditions of heavy grazing.

A final consideration is the exploratory work done by Riley and Isbell (1963) on paper chromatography in the Aloineae. Here it was suggested by way of demonstration that H. fulva was close to H. greenii, that H. reinwardtii vars. tenuis. committeesensis Smith and possibly diminuta Smith were close, that H. reinwardtii vars. haworthii and chalwinii were similar, whereas the vars. archibaldiae, valida and H. baccata were different. If H. baccata had originated at Frazer’s Camp, the chromatograph could have been expected to show affinity to H. reinwardtii var. diminuta. Similarly on the basis of distribution and outward appearances, one would have expected diminuta to be at variance with, rather than relating to committeesensis and tenuis: the latter two also expectedly differing to some degree.

Results and Discussion: The superficial impression that might be gained from the field is that a single species complex is involved. However, three distinct entities, with the two larger of these exhibiting strong clinal trends, are apparent. The two principal entities are regarded as H. coarctata and H. reinwardtii and it is rather surprising that there is a complete break in continuity between them despite their close affinity. Conceptions based on past taxonomic treatment give no indication of this discontinuity, and varieties previously described under H. reinwardtii actually belong in H. coarctata as will be shown. Even the older species H. chalwinii resolves under H. coarctata rather than H. reinwardtii as implemented by Resende. Most existing taxa in the complex are based on size, density of leaf arrangement and on shape, size and arrangement of leaf tubercles. That these criteria are inadequate is clear both front examining variability within and between populations. and from the relation of the described taxa to one another and to field populations.

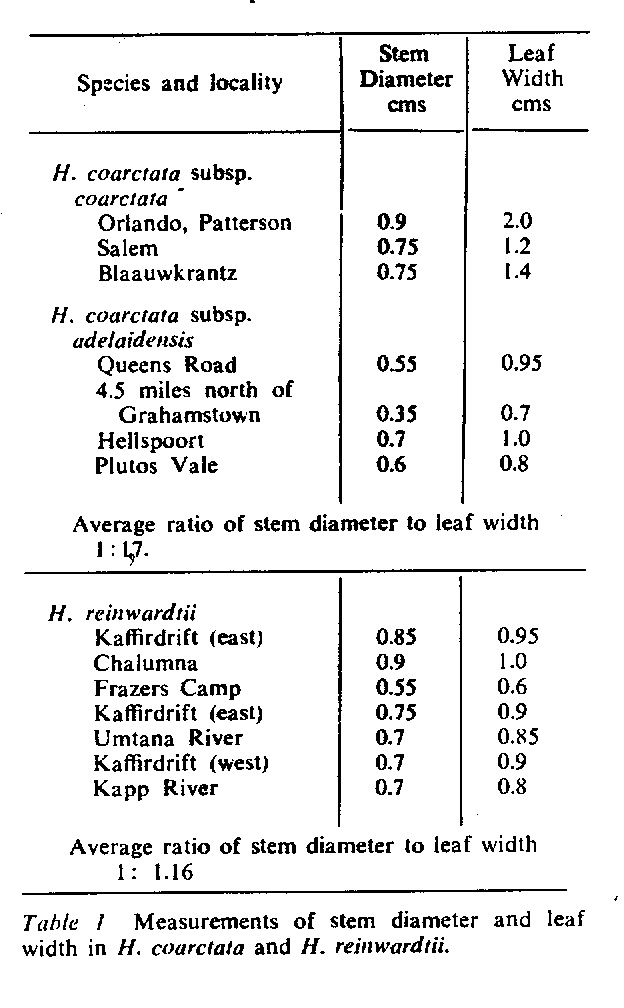

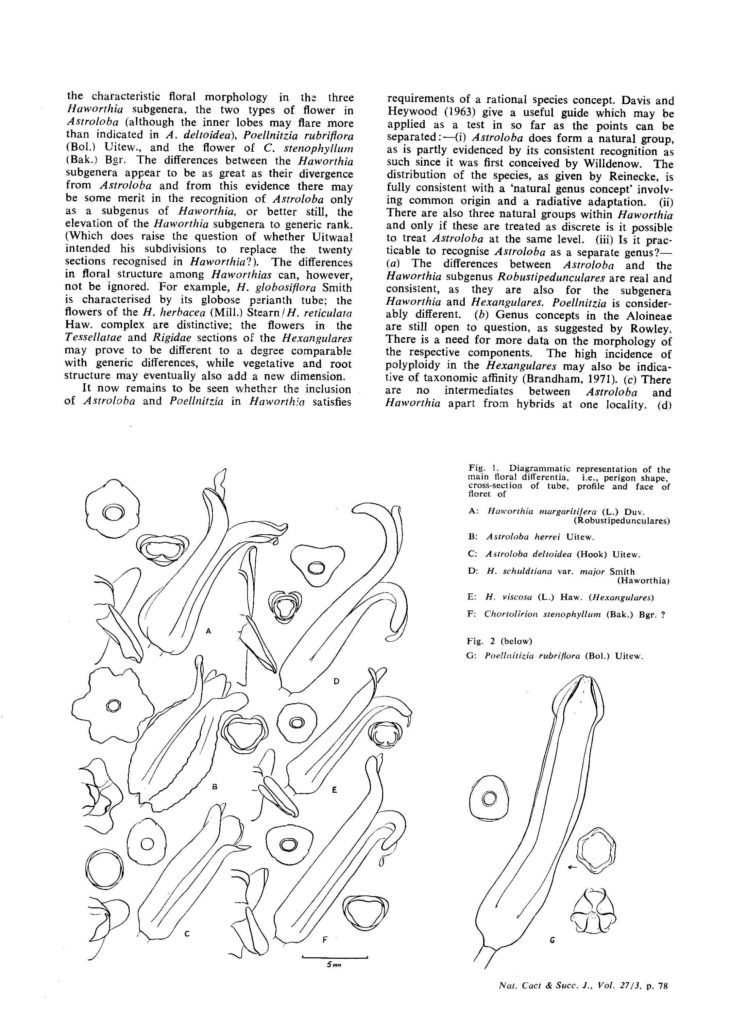

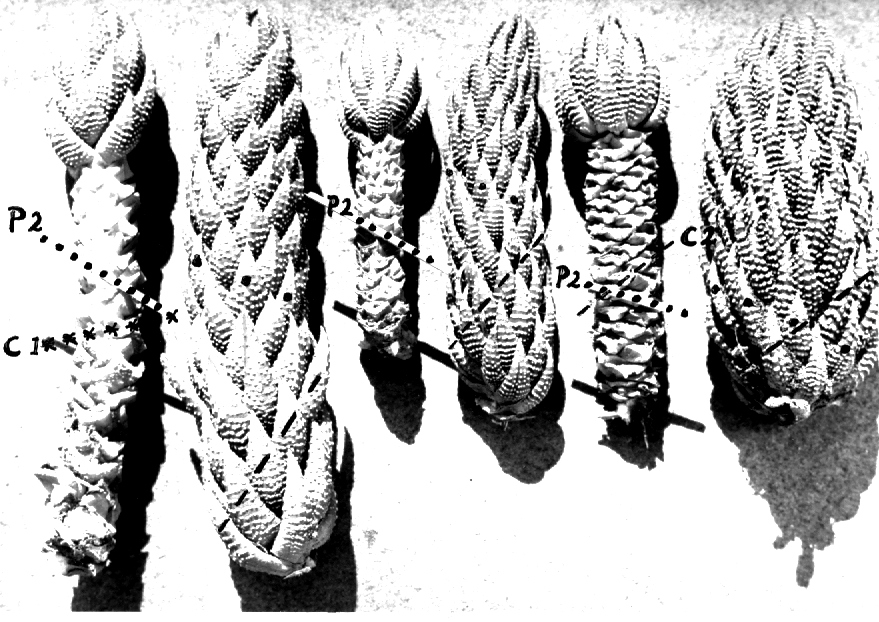

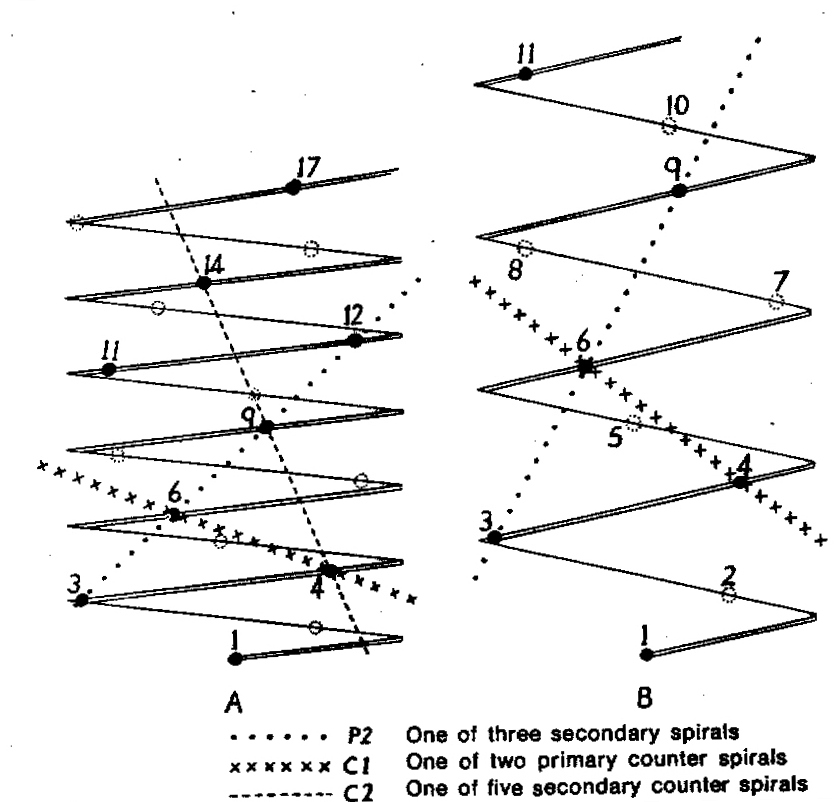

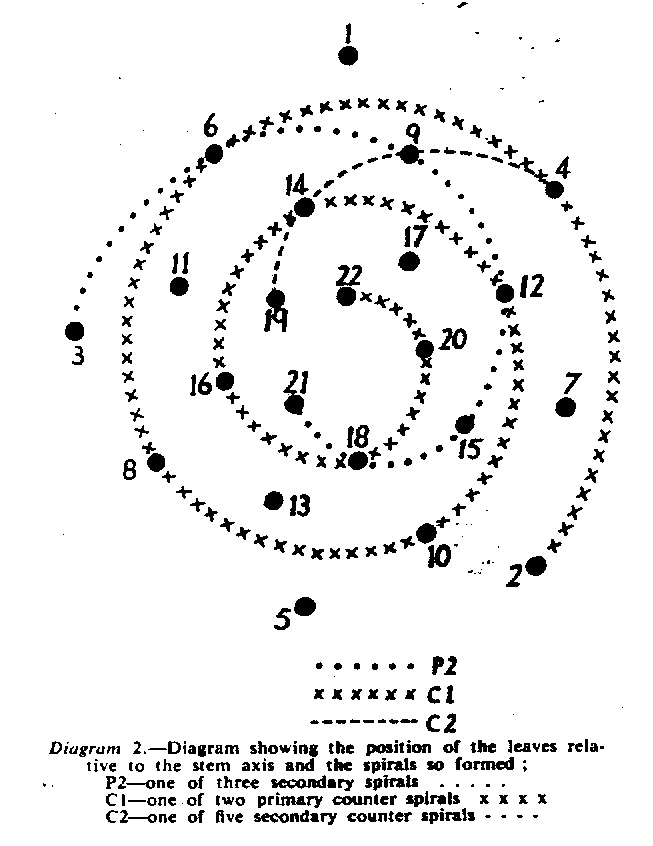

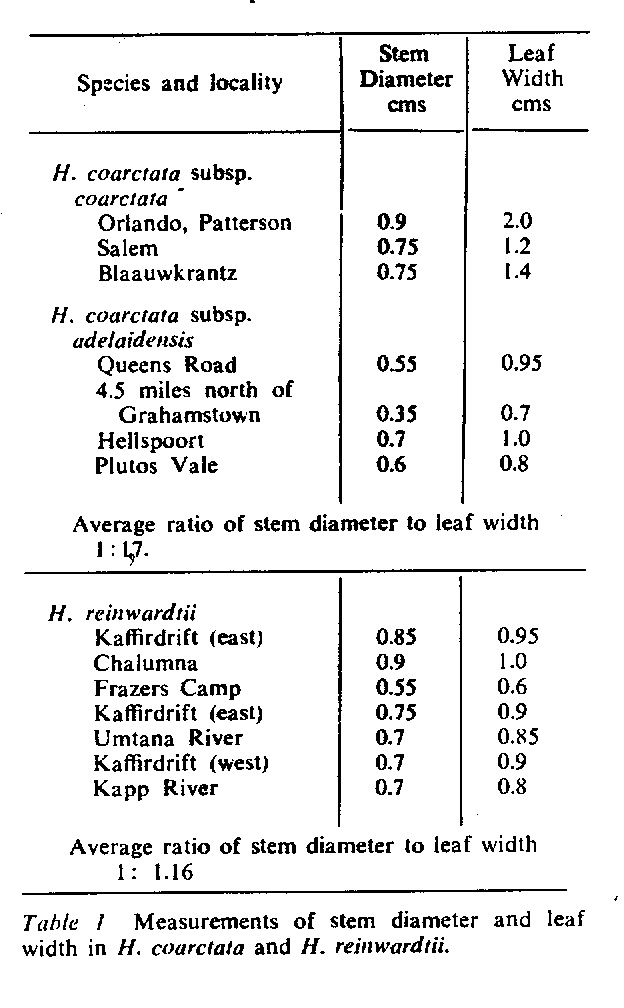

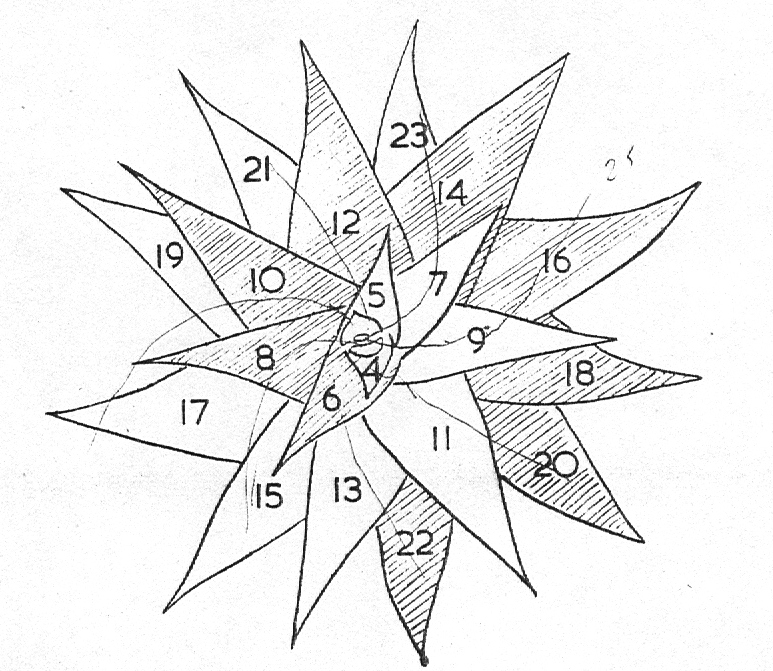

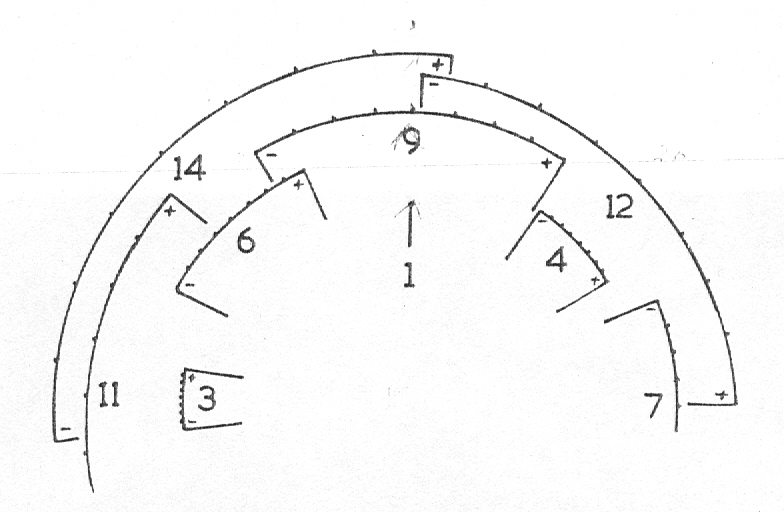

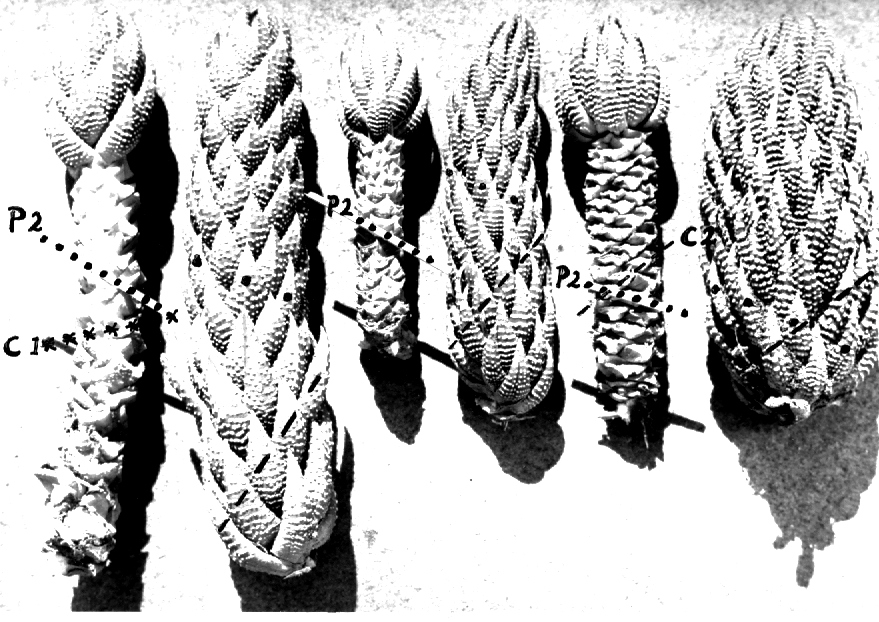

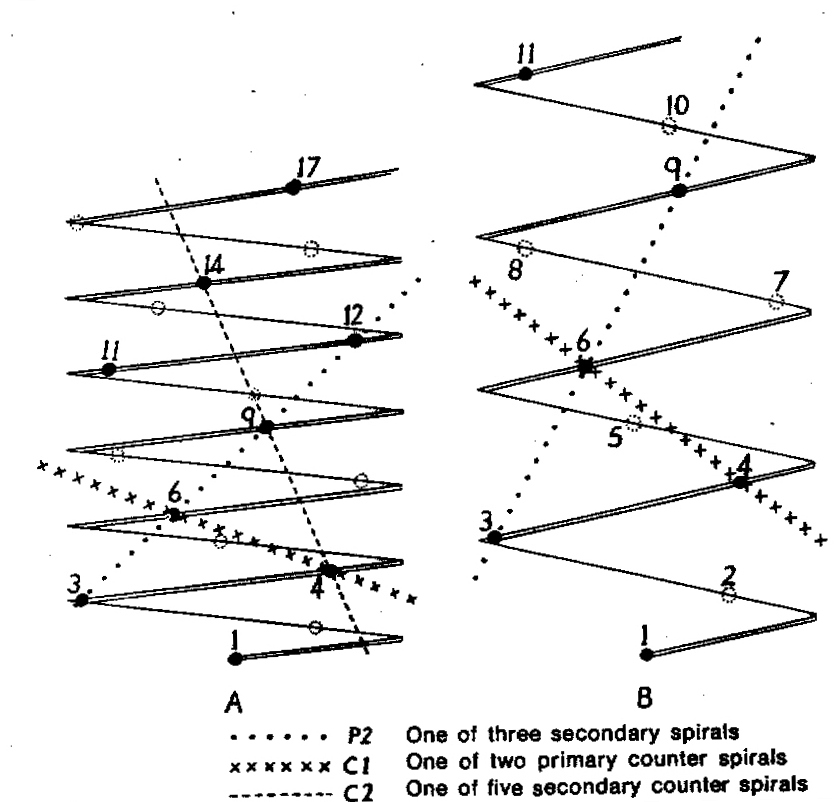

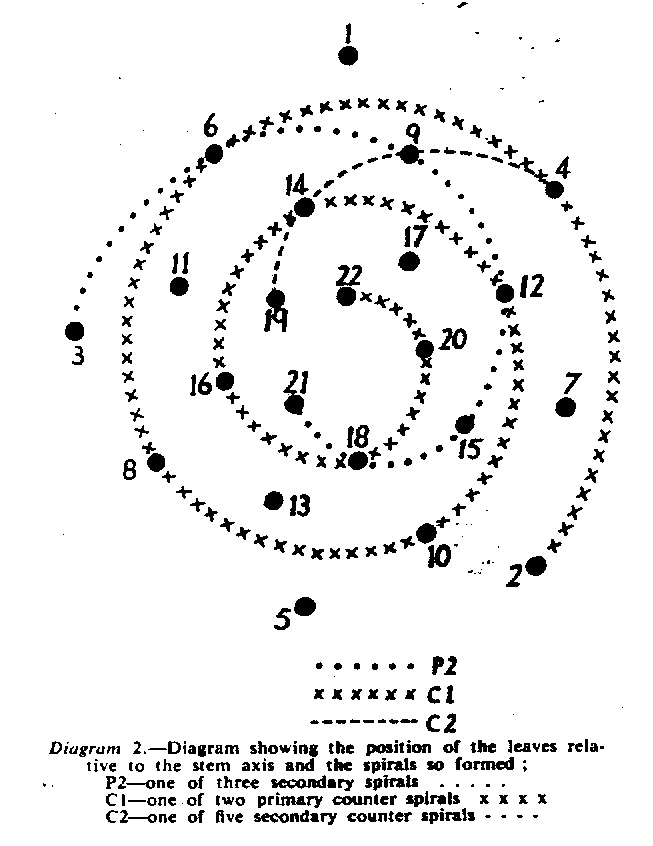

In attempting to rationalise the discontinuity between eastern and western populations in the complex, it was concluded that the general difference as associated with the spiral arrangement of the leaves on the elongated stems – a principle of phyllotaxis elaborated by Church (1904). (Church postulated that phyllotaxis is a result of fundamental growth processes and can be treated mathematically.) It is this phenomenon of spiral series which provides the device by which the two entities can be consistently and satisfactorily differentiated. By cutting the leaves at right-angles near (4mm) to the stem, these spiral rows (parastichies) can be more clearly observed. In the entity H. coarctata there are apparently 2 spirals ascending in one direction with approximately 4.5 leaves per revolution, while in the reverse direction there are 3 spiral tiers with 7 leaves per revolution. In the entity H. reinwardtii, 3 spirals with 7 leaves per revolution and 5 counter spirals with 11 leaves per revolution are seen. In fact, in both entities the leaves are arranged in a single continuous spiral about the stem, so that cutting the leaves too close to the stem precludes the configuration stated here. In both species, the leaves follow successively at an angle of approximately 137.5 degrees, so that the 22scd leaf in the spiral is again superposed over the first (the orthostichy) through 8 revolutions. The difference in spiral patterning is thus apparently an artifact which is dependant on a number of variables. These are: the ratio of stem diameter to leaf width, leaf thickness, degree to which the leaves are amplexicaul. (in effect Church’s ‘bulk ratio’), the degree of compression of the spirals on the stem, and the angles at which the leaves are subtended from the stem. The ratios of stem diameter to leaf width in H. coarctata and H. reinwardtii are 1:1.7 and 1:1.16 respectively (see table 1). The real nature of the spiralisation of leaves is shown in diagram I and 2. In H. coarctata the tiers seen on the cut leaf sections are the 3 tiers of the secondary spiral (P2 on diagram) and the 2 tiers of the primary counter spiral (Cl). In H. reinwardtii it is the 3 tiers of the secondary spiral and 5 tiers of the secondary counter spiral (C2) which are seen: the primary counter spiral ascending at such a shallow angle that the narrower leaf sections comprising it are taken for the primary spiral. The angle of ascent of the primary spiral in H. reinwardtii is half that in H. coarctata, and it is interesting to note that the maximum stem length of 26cm observed in the field, was also almost half of the 47cm observed in H. coarctata.

It must be stressed that growing conditions may possibly affect the angles of ascent of the leaf spirals to some degree, so that thicker, fleshier leaves in a specimen of H. reinwardtii may produce a likeness to a specimen of H. coarctata grown under hardy conditions. In the writer’s experience of the plants in the field and under cultivation, the distinction between the two species on this basis is absolute, and it is confidently expected that a statistical evaluation of stem and leaf dimensions will verify this conclusion. It should be noted that in the section Trifariae. the 3 leaf spirals are the secondary spirals (leaves 1-4-7- . . . ). In Astroloba and Poellnitzia, the 5 spirals are secondary counter spirals (leaves 1-6-11- . . . ). A plant of H. margaritifera (L.) Duv. at the Karoo Garden has the leaves in 8 spirals – the tertiary spirals (1-9-17- . . .), while even the distichous leaves in H. truncata Schon. are arranged in a spiral series (the primary counter spiral! The leaves are arranged spirally in all plants and whether the spirals impress visually or not depends on the width and thickness, curvature, nature of attachment, and density of the leaves on the plant stem.

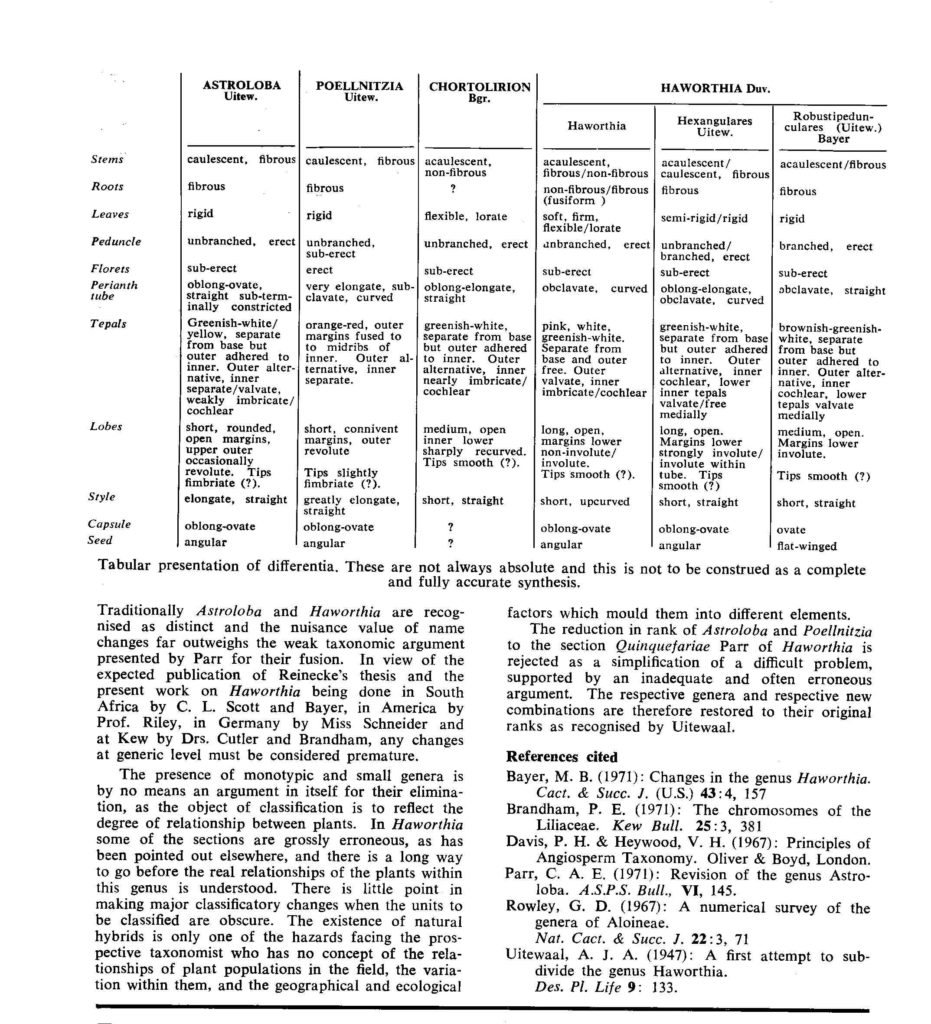

The distribution of the principal entities recognised in the present study is shown in the accompanying map. In H. coarctata, very large forms exist as populations in the vicinity of Patterson, Alicedale, Hellspoort and Fort Brown. Intermediate forms occur south and west of Grahamstown. and smaller forms in the Bathurst-Alexandria area. The Hopewell population is not such an extremely heterogenous one as earlier notes suggest, and localities on the Kowie River at Vaalvlei and at Blaauwkrantz Bridge near Manley Flats display perhaps greater variability. H. reinwardtii var. tenuis represents a distinct discontinuity and is upheld in the species H. coarctata, in the absence of further known populations, at varietal level. H. fulva, H. musculina and H. reinwardtii var. committeesensis do not represent marked discontinuities, and the same is true of H. reinwardtii var. chalwinii. The latter appears to be an admittedly rather di€tinctive form, but which appears in various population of H. coarctata including the entity tenuis. H. greenii at Howiesonspoort is recorded as both tetraploid and aneuploid and is a notable variant although clear population discontinuity does not occur. Its tetraploid state does not necessarily suggest taxonomic separation from the main body, H. coarcata, where diploid to hexaploid states are known. H. peacockii with its submersed tubercies is considered to be a local variant at Howiesonspoort and is rejected taxonomicall, while H. greenii is upheld at varietal level only. With the rejection of H. chalwinii at any level above that of forma, H. coarctatoides receives similar treatment. H. reinwardtii var. conspicua is rejected as a form of H. coarctata as many plants agreeing reasonably with Von. Poellnitz’ description were seen, but not constituting discrete populations.

H. reinwardtii var. huntsdriftensis Smith represents something of an anomaly. In the Compton Herbarium, Smith 6818A from “n hill at top Hunt’s Drift, last cutting on west side of Fish River” is clearly H. coarctata, as is Smith 7105 – “top Hunt’s Drift, west side”. Smith 6818 and 68l8B are from “on hill on top of Huntsdrift just before valley before Frazers Camp”, and these may be specimens of H. reinwardtii. Smith 3849 “west side of Hunt’s Drift” is an isotype and Smith 7106 “top Huntsdrift near Frazers Camp” is very similar. There is in all cases a lapse of 4-5 years between collection date and herbarium labeling except for Smith 7106, one year. If Smith’s detailed locality for the variety “in hollow before last hill going up to last gate at top Hunt’s Drift” is correct, then plants collected by the writer at this locality are at variance with the described taxon. Either this is due to (a) phenotypic changes brought about by cultivation—which is discounted, (b) errors between collection and recording – and there are six herbarium sheets involved, or (c) there is an additional point not located by the writer where H. coarctata is in close proximity to H. reinwardtii.

The question of phenotypic change is rejected as almost without exception herbarium specimens agree with current field collections. Exceptions are one specimen labelled “25 miles from Port Alfred to Alexandria”, which is the actual distance between these towns; and the specimen agrees with plants of H. reinwardtii collected at a distance of about 5 miles along that road. Another exception is Smith 7349 labeled “4-5 miles between Riebeek East and Alicedale” which is a blatant misfit, matching rather specimens from the eastern limits of the distribution of H. reinwardtii and Smith 5218, an isotype of H. reinwardtii var. riebeekensis Smith, labelled “4 miles before Riebeek East from Alicedale” whereas in Smith’s field book the locality is recorded “4.5 miles before Riebeek East from Carlisle Bridge”. These few discrepancies in all the herbarium specimens (263 sheets) do not allow the supposition that either phenotypic change or incorrect labeling are responsible. Plants which do match Smith’s description occur at Hunt’s Drift on the east bank, and it is likely that they are also found nearer Frazers Camp. This may prove important in future studies on this group. H. reinwardtii var. huntsdriftensis is considered to belong to H. coarctata.

H. reinwardtii var. bellula Smith is another anomaly, as a close search of the type locality, and near localities, failed to produce matching specimens. What very small specimens were seen were taken to be suffering under adverse growth conditions, and the population at this locality falls into a series extending from Bothas Ridge and Queens Road northeast of Grahamstown, to Hellspoort and Riebeek East. The Queens Road locality is the type locality for H. reinwardtii var. adelaidensis VP as pointed out to Smith by the finder, W. F. Armstrong. This is one of Von Poellnitz’ unfortunate errors where a locality has been attributed to the collector’s address rather than to actual field origin. At Hellpoort there is the case of a smaller, densely-leaved entity coexisting with a more typical population of H. coarctata, albeit not precise superimposition of locality. This fact coupled with morphological criteria, is the basis for recognition of the taxon H. coarctata. subspecies adelaidensis, which includes the populations from which the H. reinwardtii vars. bellula and riebeekensis were drawn. In the latter case, Smith’s field notes were found to be confusing and the site at Willowfountain north of Riebeek East could only be located by cross reference to noted landmarks and two other species recorded from the near vicinity.

Generally in H. coarctata the tubercles are nearly smoothly rounded and smaller than in H. reinwardtii, where they are frequently large and flattened scale- like. Also in H. coarctata there are more tubercles across the width of the leaf than in H. reinwardtii. Between Salem and Alexandria, southwest of Grahamstown, there is one particular population of H. coartata with much larger tubercies and also very densely tubercled on the leaf face. However, this is not clearly discontinuous if other populations are also considered and a new taxon is not proposed.

The distribution of H. reinwardtii can be traced from Kaysers Beach near East London, to a point west of Port Alfred, then northward to Frazers Camp and Coombs and eastward to Peddie. Local populations appear to some extent more consistent than in H. coarctata but discontinuities are not readily discernible. H. reinwardtii var. major is a form which can be found at several localities, and H. reinwardtii var. chalumnensis is reasonably regarded as one of these. H. reiiiwardtii vars fallax, valida. kafferdriftensis Smith, pulchra VP and grandicula Smith similarly have no reasonable basis on the grounds of population discontinuities. The same is true of the var. peddiensis which, in the absence of field material, it was necessary to compare the described taxon and the living type with populations nearer to the Fish River. H. reinwardtii vars. zebrina Smith and olivacea Smith are distinctive forms in a notably variable population and it cannot be considered that rank above forma is necessary or desirable. In the case of H. reinwardtii vars.brevicula Smith and diminuta, the taxa are drawn effectively from the same population at Frazers Camp. If it was necessary to apply an appellation to this fairly extensive population, perhaps the name H. reinwardtii var. minor Baker would be more appropriate at the extreme of a clinal trend in size-reduction from southeast to northwest.

In H. baccata the specimen Smith 3572 (NBG) is an isotype dated July 1944 and agrees reasonably with Smith’s illustration. Another isotype, Smith 3572 (BOL) dated November 1945 does not agree with the previous specimen, but does conform with specimens from Frazers Camp. As Armstrong, who knew the collector, Mr McClaren, maintains that H. baccata originated at this locality, the name is rejected as superfluous. The locality of H. reinwardtii var. archibaldiae is, on the basis of specimens submitted to Smith by Miss G. V. Britten (of the Albany Museum, and a contemporary of Miss E. Archibald), taken to be at the Umtana River east of Wesley in the Peddie district. Only four clones were located in a brief search at this site and this scarcity may be attributable to it being a sterile triploid. Smith identified several plants from other localities as this taxon and Von Poellnitz also recorded two localities – the varietal rank is not upheld.

Conclusion: The separation of H. reinwardtii and H. coarctata on the basis of morphological criteria, also satisfies geographical requirements. Local populations in each species, and particularly in H. reinwardtii, tend to have distinctive facies but discontinuities between populations are seldom marked. It is the writer’s opinion that colouration and general condition of the plants, imposed by local environmental conditions contribute greatly to this phenomenon of local ecotypes, obscuring more basic similarities between populations. A key for separation of varieties, as presented by Von Poellnitz, may have been workable in a collection comprised only of those particular forms, but not as a basis for usefully or consistently distinguishing field collected material. The diagnoses by which the described varieties of H. reinwardtii were to have been distinguished from one another can often be totally discredited by inherent variability at each point of origin. It is a basic tenet of taxonomy that all individuals must be referrable to a species. If lesser ranks are recognised in these species, it is logical to expect that in the same way individuals will all be referable to these categories and the parent species not treated as a repository for all forms which do not conveniently agree with descriptions.

Believing that the present exposition satisfies these requirements, the writer’s concept of H. coarctata and H. reinwardtii is as follows:-

Haworthia coarctata Haworth in Phil. Mag. 44: 301 (1.824).

Aloe coarctata (Haw.) S-D. Monogr. S6, f. 17 (1836-49).

Haworthia chalwinii Marl. et Berg. in Notizblau Berl. Bot. Gart. 4: 247 (1906).

Haworthia reinwardtii var. conspicua VP. in CJ. 5:31 (1936).

H. reinwardtii var. committeesensis Smith in Jl SA. Bot. 9:93 (1943).

H. fulva Smith in 15.4. Jl SA Bot. 9:101(1943).

H. greenii var. silvicola Smith in Jl SA.Bot. 9:103 (1943).

H. reinwardtii var. huntsdriftensis Smith in Jl.S.A. Bot. 10:14 (1944).

H. reinwardtii var. chalwinii (Marl. et Berg.) Resende et Pinto-Lopez in Port. Acta Biol. (B) 2:175 (1946).

H. coarctatoides Res. et Lopez nom. nud. in Port. Ada Dial. (A) 2:175 (1948).

H. musculina Smith in JS.A. Bot. 14:43 (1948).

Plants with fibrous elongate leafy stems from 5 to 47cm long, overall diameter from 2 to 7cm; leaf length from 2.5 to 7.5cm, width from 1.0 to 2.4cm, thickness from 0.2 to 0.8cm; ratio of stem diameter to leaf width in region of 1: 1.7; leaves ascending- spreading, multifarious incurved, broadly lanceolate to ovate-deltoid, broadly amplexicaul; back of leaves rounded, slightly keeled above, beset with numerous small rounded tubercles; face generally flat to concave, seldom tubercled.

Haworthia coarctata subsp. coarctata var. greenii (Baker) Bayer comb. nov. –

H. greenii Baker in Journ. Linn. Soc. 48:202 (1880).

H. peacockii Bak. in Journ. Linn. Soc. 48:202 1880.

Plants with stems up to 15 to 20cm long, overall diameter up to 5cm, tubercles mostly suppressed or absent.

Haworthia coarctata subsp. coarctata var. tenuis (Smith) Bayer comb. nov.

H. reinwardtii var. tenuis Smith in Jl.S.A.Bot. 14 :51 (1948).

Plants with narrow elongate stems up to 44cm. overall diameter 2.5cm, leaves up to 3.2cm long , 1cm wide.

Haworthia coarctata subsp. adelaidensis (VP) Bayer comb. nov.

H. reinwardtii var. adelaidensis VP in Succ. Afr. 3:82 (1943).

H. reinwardtii var. riebeekensis Smith in Jl. SA. Bot. 10:16 (1944).

H. reinwardtii var. bellula Smith in Jl.S.A.Bot. 11:70 (1945).

Plants with stems from 5 to 15cm long, overall diameter up to 3cm, leaf length 2.5 to 3.5cm, width 1.0 to l.lcm, thickness 0.2 to 0.3cm. Leaves are proportionately longer and narrower than in type, while stems are more elongate and thinner overall than in corresponding specimens of H. reinwardtii.

Haworthia reinwardtii Haworth

Suppl P1. Succ., 57 (1819).

Aloe reinwardtii (Haw.) S-D. Monogr. S6, f16 (1836-49)..

H. baccata Smith in Jl.S.A. Bot. 10:20 (1944).

(Included in synonomy are the varieties of this species described at various times by Von Poellnitz, Smith and Resende which have not been located elsewhere.)

Plants with fibrous elongate leafy stems from 5 to 26cm long, overall diameter from 2.5 to 6cm, leaf length from 2 to 4.5cm. width from 0.7 to 1.5cm. thickness from 0.2 to 0.35cm; ration of stem diameter to leaf width in region of 1:1.16. Leaves ascending – spreading multifarious, incurved, lanceolate, narrowly amplexicaul; back of leaves rounded, slightly keeled above, beset with large flattened scale-like white tubercles generally arranged in transverse rows, face flat, often sparsely tubercled.

(Note: It is proposed to maintain all specimens collected during the course of this investigation at the Karoo Botanic Garden, so that in due course the above classification can be verified or revised. Floral morphology has not been considered as a source of characters as the similarity or floral structure in the subgenus Hexangulares Uitewaal suggests that a very meticulous, time-consuming study would be required to prove the worth as a taxonomic aid. It is also suggested that the above arrangement based on vegetative characters may provide a working basis for further investigation in this complex. For collectors it is suggested that deposed varieties be regarded as formae in the respective species, as there is no doubt that specimens such as ‘zebrina’ and ‘olivacea’ are striking collectors’ pieces.)

Acknowledgement: The writer gratefully acknowledges the encouragement and assistance received from the Curator of the Karoo Garden, Mr F. J. Stayner, and also the assistance and hospitality of Mr D. A. Timm of Vaalvlei, Grahamstown, during the course of field work.

Literature cited:

Riley, H. P. The Nucleus, Seminar on Chromosomes (1968).

Riley,.H. P. and Mukurjee, D. The Nucleus 8:2 p. 149 (1965).

Riley, H. P. and Majumdar, S. K. Botanical Gazette 127:4 p. 239 (1966).

Resende and Pinto-Lopez, I. Port. Acta. Biol. (B) 2:178 (1946).

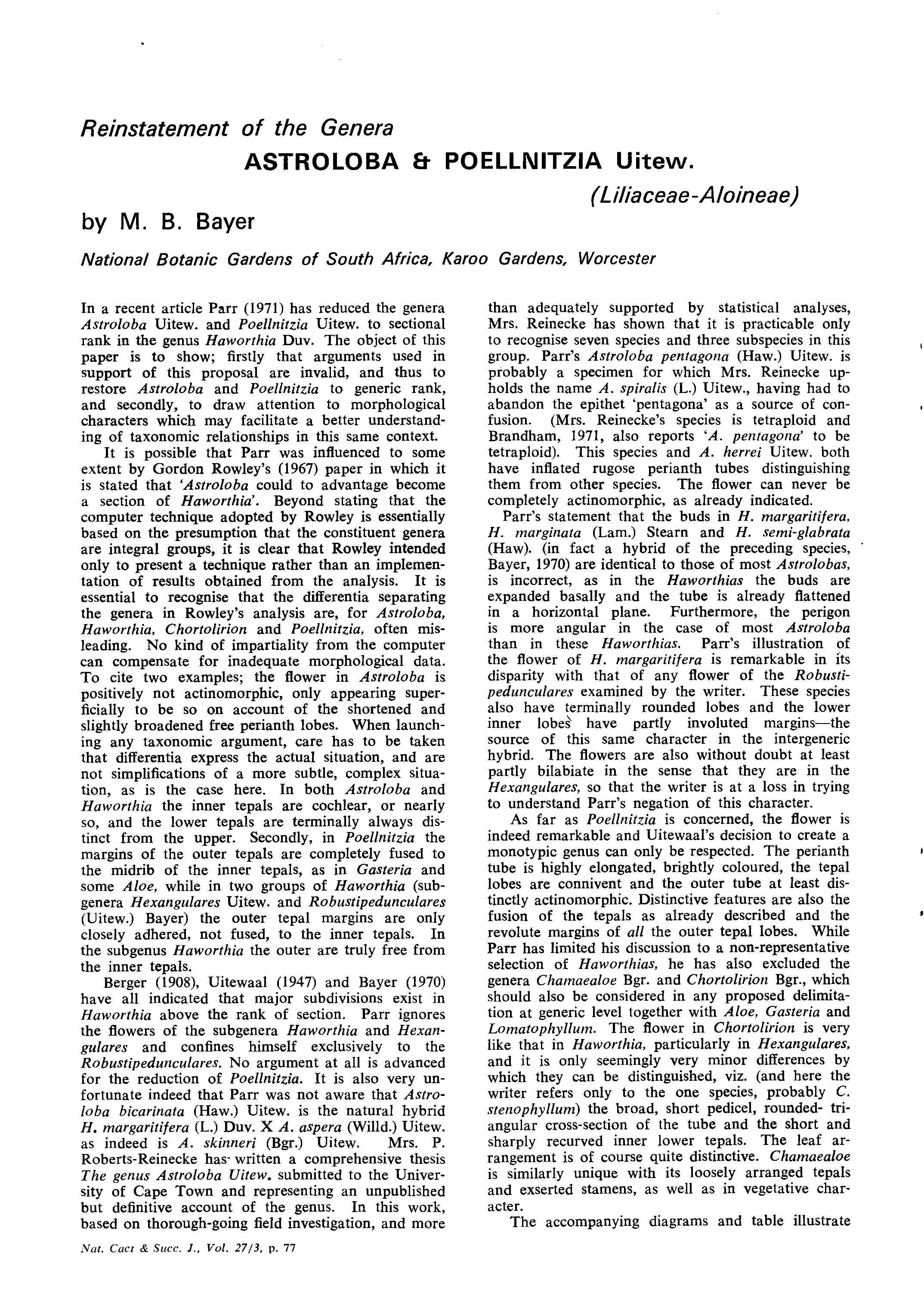

- Fig. 1 Photograph of principal entities to show secondary spirals:-

Left: KG 31/64 H. coarctata subsp. coarctata. Biaaukrantz

Centre: KG 39/65 H. coarctata subsp. adelaidensis. Queens Road

Right: GGS 7346 H. reinwardtii. east of Fish River

- Diagram 1. Diagram showing the different angles of the leaf spirals in (A) H. reinwardtii where the low angle of the secondary counter spiral approximates that of the primary spiral in (B) H. coarctata.

- Diagram 2. Diagram showing the position of the leaves relative to the stem axis and the spirals so formed.

P2 – One of three secondary spirals

Cl – One of two primary counter spirals

C2 – One of five secondary counter spirals

- Diagram 3. Map showing the distribution of:-

C – H. coarctata subspp. coarctata var coarctata Haw.

CG – H. coarctata subspp. coarctata var greenii (Bak.) Bayer.

CT – H. coartata subspp. coarctata var tenuis (Smith) Bayer.

CA – H. coarctata subspp. adelaidensis (V Podia.) Bayer.

R – H. reinwardtii Haw.